How Trees Support Learning with Albert Garcia

Have you ever noticed that tree-lined streets and neighborhoods with lots of trees seem appealing? Have you ever thought that your school or the area around campus could use more trees? Well, it turns out that trees do more than just make things look nice: having a lot of trees on campus and near a school actually improves achievement (yes for real!). In this episode of The Thoughtful Teacher Podcast Albert Garcia shares research that directly connects a fuller tree canopy with improved student achievement and he tells why planting trees is one the strategies for student success.

Listen Now! (direct link to episode)

Episode Links

Global Environmental Change journal website

University of Utah story about the study

Transcript

Scott Lee: Greetings friends and colleagues, welcome to The Thoughtful Teacher Podcast, the professional educator’s thought partner-a service of Oncourse Education Solutions. I am Scott Lee. If you would like to learn more about how we partner with schools and education organizations please visit our website: www.oncoursesolutions.net and reach out.

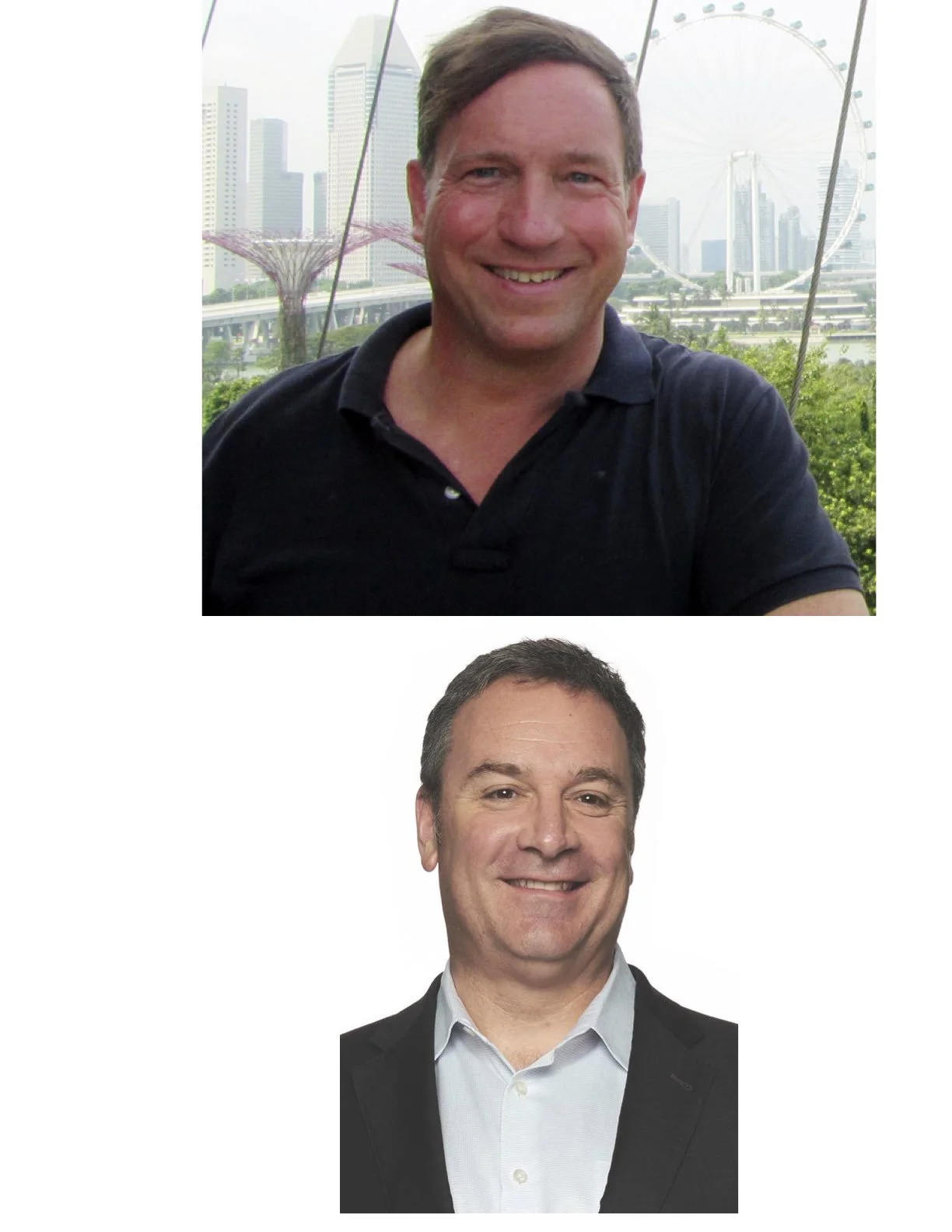

In this episode I am sharing a conversation with Albert Garcia. Albert is an assistant professor at the University of Utah who teaches and conducts research in the departments of economics and the School of Environment, Society and Sustainability. In this role, he studies the connections between economics and livelihoods which leads him to research projects on environmental policy, land use and the human impacts of environmental change. His work came to our attention because he co-authored a recent publication studying the connection between trees and student achievement, which we will discuss in this episode.

Welcome Albert to the thoughtful teacher podcast.

Albert Garcia: Thanks, Scott. Really excited to be on today. Thanks so much for the invitation to chat.

Scott Lee: So first off, can you tell us a little bit about what you do and what your areas of study focuses on?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, so I'm trained as an economist and specifically an environmental economist, and a lot of my work falls into, I'd say, two distinct themes.

The first is evaluating the efficacy or effectiveness of environmental policies to yield the expected or desired outcomes there. And so, a lot of that work is actually looking at forest or biodiversity conservation policy, a lot of times outside of the U. S., a more global area of study that work tends to be a little bit more global in nature.

Then the second theme is more in line with the study I'm going to be talking a little bit more about today. And that's estimating the human or social impacts of environmental change, and how those two sort of intersect. And so that's the theme that I'd say this study falls into, and excited to talk more about that.

Scott Lee: Okay, we'll get to that study here in just a few minutes. But first off, since a lot of our listeners are teachers if you could just tell why an economist is interested in education in particular, you talked about why an, an economist would be interested in the environment, but what about education?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, for education, I think, it does a lot to shape many of the big picture outcomes in our lives, and those outcomes could be either individual, but also societal in a lot of ways, so things like inequality, upward mobility, and economic growth are all things that are shaped by the individual.

individual and societal education, all of which are things economists really care about. And I think you can think of education not only as this intrinsic good that a lot of us like to think of it as, but also something that's really important to our economy and also our personal economic situations.

Scott Lee: Mm hmm, so how did you and your co-author come up with the idea of studying how invasive species could affect K 12 learning? That still seems a little bit kind of out of left field.

Albert Garcia: Yeah, absolutely. I think that's fair. I think it all sort of built on it itself a little bit. So, I sort of started out with we know that trees provide substantial benefits and especially in cities, the most salient of those benefits might be pollution reduction or extreme heat mitigation, and they might provide some psychological benefits, some mood boosting just by having green space around and recent work in economics has done a really good job of identifying the impacts of some of those environmental factors on learning and other student outcomes.

So specifically, there's been some good work on identifying the effect of heat and pollution on student test scores and attendance rates. And I personally have been interested for a while in trying to figure out a way to estimate the impacts of tree cover on social outcomes more broadly in a causal fashion.

And so, economists are really interested in what's called causal inference, trying to disentangle causality from correlations. And in this context with tree cover, it's particularly hard to do. So, there's very little work outside of laboratory settings that are actually able to do a good job of establishing a causal relationship. And this invasive species that I'll talk about later, sort of allowed for a natural experiment to get a little closer to that, but after some brainstorming with my coauthor, Michelle [Lee], we thought that students were a group that could be particularly vulnerable or affected by a lot of these environmental nuisances such as pollution or extreme heat, and we thought particularly young students who were still developing cognitively could be impeded either more permanently or more quickly than a lot of other populations.

So yeah, we were really excited to be able to learn more about sort of the Illinois school district and how they administered standardized testing and get data on that. And once we actually dug into it, we found that there really wasn't a lot of work. Looking at the effect of trees on education outcomes in a causal fashion.

Scott Lee: So, what you all studied is an invasive species. Before we talk about the study specifically and the results, if you could share just a little bit about what the ash borer is and what it does to trees in Chicago, which is where you conducted your study?

Albert Garcia: And so, a lot of times what we see is that, well off areas tend to have a lot more trees, as well as higher education outcomes. So, the correlation between trees and education outcomes tends to be positive.

Areas with high tree cover tend to have better education outcomes, but it's not necessarily the case that that's because there's more tree cover. It could just be because those communities have more resources to plant more trees, engage the Department of Forestry to come to their area, more willingness to sort of engage with those, parts of their community, perhaps.

And so, the difficulty is actually saying, “What's the impact of the trees on education outcomes?” And this is where this natural experiment by the arrival of this invasive species, the emerald ash borer, really helped us to sort of figure out what was due to that correlational component and what was actually due to the presence of tree cover in those communities.

And I'll talk a little bit about the ash borer. So, uh, Michelle is more of the ecologist entomologist part of the team, but I'll do my best here. Essentially the emerald ash borer is a metallic green beetle that's native to Northeast Asia, and it feeds specifically on ash species. So, ash trees and it was introduced to the U.S. in 2002, first found in Michigan. And in its native area out in northeast Asia, it doesn't really tend to do too much damage to the specific species of ash that are in those regions. But here in the US, the specific species we have, it's been extremely destructive to the ash species and the broader tree populations in a lot of cities that use ash as one of the primary arc and street trees in metropolitan and urban areas.

And infestation by the ash borer for these U. S. ash species is essentially fatal to any infested tree and over the course of these last two decades since it's been in the U. S., it's led to the death, decline, or removal of tens of millions of trees in the U. S., and a lot of that's been concentrated in the midwestern U. S. Especially those cities where ash has made up the majority of the street and park trees.

Scott Lee: I was just thinking as an aside, being in, in Tennessee where ash is not as common you don't see a grove of ash trees, like you see groves of maples and, and oaks here. So, it hasn't affected a lot of other places like it has in the Midwest then?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, absolutely. And in some of these Midwest cities, like Chicago, you can really see it. These really large ash trees that might be providing like, 10 meters, 30 feet worth of canopy cover diameter, and then just losing those really large mature trees could have a really big impact on just the feel of a given street.

Scott Lee: It, it's kind of surprising that, that you were able to connect the loss of ash trees to K 12 achievement. And, you did that by comparing state testing data to locations where the trees disappeared is that correct?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, that's pretty much right. So yeah, here we're focusing specifically on the Chicago metropolitan area, which has been hit particularly hard by the Emerald Ash Borer. And in Chicago, ash were really the most common street park tree prior to the ash borer's arrival in 2006, but it's killed or led to the removal of about 10 million trees in the Chicago metropolitan area essentially halving the ash population. And like I mentioned, a lot of these are really large, mature trees that were cut down, so you can really, really feel the difference between a street with several really large, majestic ash trees and then just a bare street afterwards. And some of those trees might have been replaced by small saplings, but it's going to take decades for those trees to really get to the stage they were at before the ash borer killed them.

Scott Lee: So, it takes several decades for an ash to grow and mature, is that correct?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, a lot of these trees that were removed because of these infestations were several decades old canopy cover and had really massive trunks.

Scott Lee: What specifically did you find as far as achievement goes compared to the destruction of the ash trees?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, and so I guess with the ash borer's arrival, it wasn't something that happened like all of Chicago immediately had ash borer and all the trees sort of died at once. It was introduced and then slowly spread through the region and a lot of that was pretty idiosyncratic spread where perhaps the ash borer hitched a ride on a vehicle and sort of a satellite population spurred up in another part of the region.

And so, we're really trying to take advantage of that staggered and idiosyncratic spread of the beetle throughout the region and take advantage of the fact that it's pretty hard to predict where it's going to show up next a lot of the times and so we first compare tree cover in areas where ash borers arrive after the arrival of the ash borer relative to areas where it actually hasn't shown up yet.

And so, we see after the ash borer's arrival, tree cover starts to decline in those areas relative to the areas where it hasn't yet shown up. And we apply that same approach to test scores. So, after the decline of tree cover, that's been induced by the arrival of this ash borer. We find that test scores experience a bit of a dip in those same areas, especially when those infestations are in the direct vicinity of a school.

Scott Lee: So, if I understand this right, you basically have a map of where the, the tree, the ash trees are dying and having to be cut down or they're being cut down because they realize the, the ash borer is there. And so, there's a lot of canopy loss and you can compare that to the map of the school zone, correct?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, that's right. So, we know the actual locations of each of the schools in the Chicago metropolitan area. And so, we also know exactly where these ash borer are being detected. And we can establish that after a detection of an ash borer, the tree cover in an area declines. And we can also show that the same thing happens in the direct vicinity of a school because we know where those schools are. And then we test when those ash borer infestations are in the direct vicinity of a school. Test scores drop when that tree cover declines relative to areas that haven't yet experienced those declines.

Scott Lee: And because of that, you can actually compare test scores of schools where ash borer has hit, where the tree canopy is dropping with a similar school, where there's still good tree canopy. So you actually are able to isolate that one effect. Is that correct?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, that's right. So, you can see, for example, a lot of broadly across the region, test scores were increasing. The percentage of students across the region that met the state threshold for achievement tended to go up through time. And so, you can compare the trend in areas that saw the ash borer to the areas that hadn't yet seen it. And what we see is relative to the areas that hadn't yet seen it, we see a dip in test scores right after the ash borer shows up in that area.

Scott Lee: That's, that's just kind of amazing that, that one factor actually does affect achievement.

Albert Garcia: Yeah. And once we control for income and a bunch of other factors, you can show that the trend in that test score achievement between the schools that had ash borer infestation and those that didn't, we're really following the same path up until the point that the ash borer actually showed up and decimated the tree cover in those areas. And that's exactly when you see the, the dip and test scores. And specifically, we found that the introduction of the ash borer to a given area led to about a 1 percent decline in attainment of those standards, based on the Illinois state achievements test, which was a standardized test, given in Illinois up until 2014, I believe. And just to compare it to another recent study, this other study looked at the effect of heat on test scores, and they found that a one-degree average increase in heat over the course of a year led to a one percent decline in test scores.

So, we found essentially that the introduction of the ash in a given area or in the vicinity of a school with about the same impact as a one-degree average increase in temperatures over the course of a year.

Scott Lee: Wow. So, the loss in canopy also in a microclimate could also create additional heat and potentially start an additional domino effect because of a higher temperature within that small area you didn't study that, but I mean, that's that's the natural progression right?

Albert Garcia: So, we definitely think that part of the mechanism for why or explaining why this loss in tree cover impacted students is through that heat channel in addition to these other channels, like pollution, for instance. But we didn't actually disentangle the relative magnitude of each of the channels.

Scott Lee: Right. The “for further research” section of your study there are just so many places that, that scholars could go. It's pretty amazing.

Albert Garcia: Definitely. Yeah. And I'm excited to do more work on urban trees and education and, you know, see exactly what we can find and I guess one thing I sort of glossed over that was really interesting about the study that we found is that most of the impacts were concentrated on low-income students.

Scott Lee: So even when ash borer, affected a given school, the well-off students tended to be able to manage that and not see really any decline in test scores, and it was really only the low-income students that saw that drop.

So, is planting trees, simply planting trees, is that going to help solve the problem?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, I think trees play a huge role. You know, we're not surprised about the benefits that trees provide, especially in urban areas. But. I think a lot, like you mentioned, of this study's implications speak to larger societal issues. And I think it speaks in large part to students differential abilities to handle environmental nuisances or environmental bads. So, even beyond just increasing tree cover, I think it speaks to trying to, reduce exposure to heat for certain students. If there is a really hot playground, you might imagine that AC [air conditioning] is really important for schools. So if teachers can do more, perhaps when there's an opportunity to make those school level investments in those kind of infrastructure enhancements, those could be really impactful for individual students and learning outcomes that reduce the impact of these environmental bads and maybe reduce the inequality associated with them.

So, for example, if a low-income school doesn't have AC, but the high income school does have AC. That's when you're going to see sort of these really big disparities in education outcomes for, for different groups.

Scott Lee: Well, and, oftentimes low income schools are either smaller or in older buildings and any school, surrounded by parking lots, as opposed to a schoolyard, a green schoolyard you're, impacting, even more, the potential problems particularly for students in poverty aren't you?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, that's exactly right.

Scott Lee: So, what other actions should policy makers or K 12 teachers be taking to work on mitigating this issue based on your research.

Albert Garcia: Yeah, I think right now, so an exciting opportunity is that the U. S. Forest Service had about 1 billion in funding, that they are trying to allocate to county departments of forestry, and I'm not sure exactly with the current administration what the state of that funding is, but there was a lot of focus on trying to reduce the gap in canopy cover between different communities across those urban areas.

And so, there's a lot of opportunity. It seems to fund enhancements and improve equity and a lot of these urban communities. And I think that, it could be useful to see if your county or your department of forestry is currently engaging with any of these specific initiatives and you might be able to reach out to them and get them to prioritize certain areas, perhaps in the area surrounding schools in low income neighborhoods.

I think there's A lot of room to make an impact there. Not too many people are actually reaching out to these departments. It seems so they tend to be quite responsive. I know here in Salt Lake. You can also direct exactly where trees are planted. You can call and the Department of Forestry will come and plant a tree in front of your house.

If you just make that call and request those trees. And I know Chicago has, and I think there's similar initiatives there. So, on an individual level, I think it's possible to actually get trees in your neighborhood. It'll take a while to mature, but over the long term, those decisions could make pretty large, differences in the feel and tree cover in a given community.

And one example I'll highlight there is just that Chicago or Salt Lake City here in the, in the city has actually quite a surprising amount of tree cover in the neighborhoods, but the moment you go to those suburbs, it's quite barren, and a lot of that is just trees were actually planted here a couple decades ago, whereas those suburban areas, that wasn't the case, and now that it's been a few decades, you can really see huge differences in both The heat in those neighborhoods, as well as just the broader feel.

Scott Lee: So also, I guess, developers should not cut down, clear cut, areas to build houses. They should only cut down the necessary trees, I guess, too.

Albert Garcia: Yeah. I am not exactly sure what goes into the decision making for developers, making those developments, but ideally for the residents who end up living in those communities, that would be ideal,

Scott Lee: More trees are almost always good. So, tell us where your study is actually published. We'll be sure and put a link on the website to it as well.

Albert Garcia: Yeah, so the study was in the December issue of Global Environmental Change, which is an interdisciplinary social science journal that focuses on interactions between society and the environment.

Scott Lee: Okay. And what are some other resources that you could suggest for folks?

Albert Garcia: Yeah, I think what I learned a lot from is just local Department of Forestry and emerald ash borer sites, so it's really interesting. They have scientists who have really done a good job of communicating what's necessary to know and what's digestible to learn about tree cover in your own area, as well as what the value of that tree cover it could be.

So, a lot of departments are rolling out initiatives to try to map the actual monetary value of trees in your community based on all the ecosystem services they offer. And I think it's really interesting to check that out. And not only just learn about it, but use it as a, as a tool to, argue and advocate for more tree cover and more equity in your own community.

Scott Lee: And the types of trees should be native as much as possible too, I guess.

Albert Garcia: Yeah, or at least, I think there was a Dutch elm disease here in the U. S. A lot of communities had majority elm trees making up their street trees. A lot of people then had a lot of ash trees, and so we've seen sort of these different diseases or invasive species come through and decimate those populations of individual trees, so at least more diversity in the species that are making up a given community.

Can do a lot for, in terms of resilience.

Scott Lee: Yeah. Here in East Tennessee, we lost all of our chestnut trees about a hundred years ago. A little over a hundred years ago. Same thing.

Albert Garcia: Mm hmm. Mm hmm. Yeah. Kind of crazy.

Scott Lee: Yeah, a lot of research on a, on a hybrid for that using, Asian chestnuts to try and bring it back, but, still they have not been successful doing that.

Thank you so much for joining us, today Albert and sharing, this really interesting and helpful study.

Albert Garcia: thanks so much, Scott. It was really fun chatting and really excited to share more about the study.

Scott Lee: The Thoughtful Teacher Podcast is brought to you as a service of Oncourse Education Solutions. If you would like to learn more about how we partner with schools and youth organizations strengthening learning cultures and developing more resilient youth, please visit our website at w w w dot oncoursesolutions dot net. Also, please follow me on social media, my handle on Instagram and Bluesky is @drrscottlee and on Mastodon @drrscottlee@universedon.com

This has been episode 4 of the 2025 season. If you enjoy this podcast, please tell your friends and colleagues about us, in person and on social media. Also, five-star reviews on your podcast app helps others find us. The Thoughtful Teacher Podcast is a production of Oncourse Education Solutions LLC, Scott Lee producer. Guests were not compensated for appearance, nor did guests pay to appear. Episode notes, links and transcripts are available at our website w w w dot thoughtfulteacherpodcast dot com. Theme music is composed and performed by Audio Coffee.